Q: In early December, the ILO and the parties to social partnership signed a new cooperation programme. What’s new in it? What is the dynamics in the development of these relationships?

A: The new Programme of Cooperation with the Russian Federation for 2021-2024 has a strong human-centered approach to the Future of Work. The Programme proposes quality investments in people throughout their working lives, in the institutions of work and in decent and sustainable work to enhance the ability of workforces to meet rapidly changing labour market demands.

It also capitalizes on the lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic, relating to innovative solutions to sustain business continuity and increased productivity. The Programme enhances the scope and depth of the social partnership by strengthening its system at all levels and facilitating social partners’ involvement in new sectors of the economy and new forms of employment.

It is a qualitative shift in cooperation between the Russian Federation and the ILO, in line with global world of work developments, that preserves and emphasizes the good relationship we already have.

Q: Sometimes it takes years or even decades from the time of the adoption of certain ILO conventions to their ratification by the Russian Federation. How do you assess this situation? Could something really change for the better in the lives of the Russian people if our parliament ratifies them faster?

A: When a country ratifies a Convention, it has a legal obligation under international law to ensure its provisions become a legal and practical reality for workers and employers. The ILO, of course, encourages ratification, but it also considers it important that countries ratify Conventions with a full understanding of its obligations and a willingness to make all the required legal and practical adjustments.

In other words, ratification for the sake of ratification is not likely to be of much practical benefit for workers. Every country should, naturally, determine which Conventions it wishes to ratify, taking into account its national priorities, and ensuring these priorities are determined in consultation with the social partners.

When ratification is the result of such a national consultation process and supports the realization of national priorities, it is likely to have the most beneficial impact for workers. It is certainly preferable that this be done quickly whenever that is possible.

Q: Two years ago, Russia ratified the ILO social security (minimum standards) Convention No. 102 with the exemption of the so-called family security and unemployment insurance. How do you feel about partial ratification of the ILO conventions?

A: ILO Conventions reflect minimum standards that all 187 Member States of the ILO should be able to implement. Bearing in mind that countries are all different, the ILO’s constituents, who together develop ILO Conventions, have considered that a certain level of flexibility is required for some Conventions, to enable ratification by as many countries as possible.

Convention No 102 is both a comprehensive and a flexible instrument. While it establishes the principles which form the backbone of social protection systems, it may be ratified upon acceptance of at least three of the nine social protection guarantees specified. This allows countries to progressively build and extend their social protection systems.

Russia accepted seven out of nine branches thereby committing to observe at least minimum levels of internationally agreed protection. As you point out, it deferred acceptance of family allowance (most often in the form of child benefits schemes worldwide) and unemployment protection guarantees to a later date.

Russia already has some elements of family benefits through the maternity capital programme, some in-kind programmes and services for children. It recently disbursed universal one–off cash transfers to families with children under 16. Having said this, the purpose of a maternity capital programme is somewhat different than the one enshrined in C102. It is hoped that in due course Russia will explore pathways to further systematise and extend, as appropriate, its child and family support programmes.

Unemployment benefits, as one segment of broader unemployment protection schemes, have proved critical in times of various financial crises, as well as the on-going pandemic. Their main objective is simple and straightforward – the provision of temporary and partial income replacement to insured people who lose their jobs.

Worldwide, some 98 countries have unemployment protection schemes which have proved to be beneficial to employers, workers and society as a whole. These returns far outweigh their minimal costs. With social security institutions in place, like in Russia, it should not be difficult to propose options for unemployment insurance to complement existing benefits in case of unemployment. Such initiatives would require legal, institutional and actuarial feasibility studies. And the options chosen should be a result of tripartite consensus.

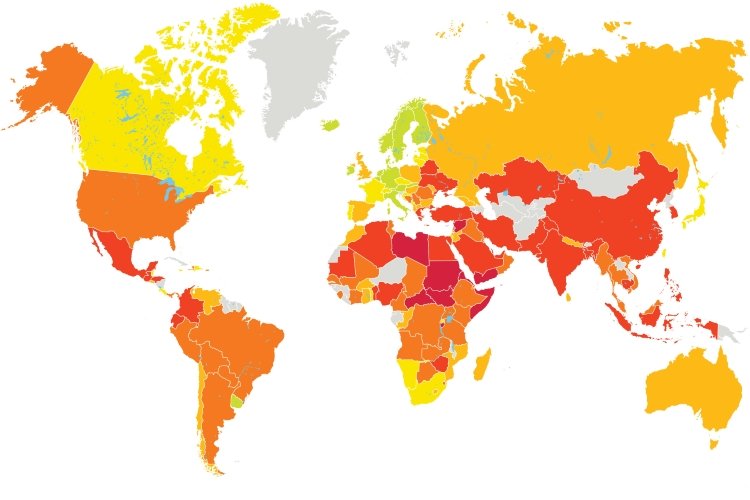

Q: What does Russia look like against the background of other ILO member states in terms of observing labour rights and providing its citizens with social guarantees?

A: Russia has a commendable ratification record, having ratified 77 out of 190 ILO Conventions, including all eight Fundamental Human Rights Conventions of the ILO. It is important to bear in mind though that ensuring full conformity with the requirements of ILO Conventions is an ongoing process for all ILO Member States. As circumstances change, so do laws and their practical application.

Social insurance is a core element of Russia’s social protection system. Efforts to extend coverage to previously unprotected population groups have been made through a combination of non-contributory and contributory schemes. It must be underlined that including previously unprotected workers into contributory social insurance schemes is essential since such coverage usually provides higher levels of protection than non-contributory, tax –financed schemes. This is also a key component of policies to facilitate the transition of enterprises and workers from the informal to the formal economy, as reflected in ILO Recommendations No. 202 and 204.

Q: Can we talk about specific nature of labour conflicts in the countries of the former USSR in comparison with Western Europe?

A: The nature of labour conflicts is determined by many different factors, including the economic policies of a given country and the way industrial relations are organized. The gradual replacement of centrally planned economies by free markets, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, has had transformational effects across Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

After 1991, many countries in the former USSR pursued investment-friendly policies using cheap labour force supplies as a comparative advantage. This approach, underpinned by a strong belief in the deregulated labour market and trickle-down economic theory, rather than by more sustainable, inclusive and decent work-led economic growth, manifested itself in serious problems for working conditions and labour rights.

This triggered tensions between the social partners at all levels of industrial relations. Therefore, it is no surprise that while labour conflicts in Western Europe can usually rely on robust resolution mechanisms, in the former USSR we have observed high instances of rights-related disputes with frequent wild-cat strikes. The larger informal economy in the east of the region is also a factor in this, as is ever-increasing competition for foreign investments.

When it comes to labour conflicts, workers in Eastern Europe and Central Asia may tend to be more cautious about their demands for improved working conditions because of their concerns about job security. By contrast, in Western Europe, achieving wage increases particularly when there has been productivity growth is likely to be more frequently the subject of labour disputes.

Last but not least, the diversification of national economies and the modernization of skills development systems have become increasingly important topics of labour relations in the East and West alike, as labour markets become more affected by rapid technological changes and automatization.

Q: In Russia, we have seen many examples of unethical and even criminal (as evidenced by a number of court decisions) treatment of local employees by international corporations. This is particularly the case in the field of trade. Is this a general situation around the world, or is it more typical of Russia? Are there any successful strategies and positive examples of fighting international corporations for workers’ rights?

A: Multinational enterprises’ responsibility for the observance of labour rights across their contractors and supply chains is one of the most important issues the ILO has been working on with its Constituents. The issue is global and is not unique to any one country in the world.

The ILO’s Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration) was significantly revised in 2017, offering to companies and employers’ and workers’ organizations more streamlined mechanisms to prevent labour rights violations in supply chains and effective responses when they happen. The Declaration says that due diligence processes and meaningful social dialogue are important in reducing human rights violations and allowing companies to contribute to the social-economic development of host countries. It allows governments and national tripartite bodies to play a role, encourages greater recognition of global framework agreements, and offers an ILO platform for dialogue to resolve disputes.

Another international instrument that addresses issues in supply chains is the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. It promotes recommendations from governments to multinational enterprises on responsible business conduct. The OECD Guidelines set standards for responsible business conduct, not just in relation to labour rights, but across a wider range of issues such as human rights and the environment.

Q: Is it possible now to predict qualitative changes in the relations between governments and trade unions due to the pandemic? For instance, recently Russia has adopted a law on remote work, which social partners generally perceive as a positive one. But it is entirely possible that other laws may worsen the workers’ situation under the pretext of protecting them from the pandemic. Are there any similar examples or forecasts? What is the ILO’s attitude to such perspective?

A: The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated labour market transformation processes through the greater use of digital technologies. The history of industrial relations teaches us that meaningful tripartite and bipartite social dialogue, that brings together Government and independent, democratic workers and employers’ organizations, is the right recipe to ensure policy decisions that facilitate greater resilience and sustainability of economies.

We have tools to make sure social justice and decent work are not just the privilege of a few, but are instead universally applicable values. The UN sustainable development agenda with its policy of Leaving no One Behind, and the ILO Centenary Declaration, promote a human-centered approach to the future of work.

The adoption of a new teleworking law in Russia is a vivid example of successful inclusive social dialogue carried out by the Russian Tripartite Constituents. I am happy that the ILO’s expert and technical support has been instrumental in this process. Rebuilding the level of representation of social partners will be the key, since the hundreds of millions of jobs lost to the pandemic might translate into higher informalization of employment relations and thus a further drop in union membership during the recovery process.

In this rapidly changing context, trade unions globally face the challenge of transforming themselves into a more inclusive movement. By extending the representation of disadvantaged and vulnerable groups in the labour market they will be able to claim wider recognition and respect for their priorities at the negotiating table.

Q: The first trade union that comes to mind in the U.S. is the teamsters’ union; it is coal miners in Britain and public sector workers in Russia. However, the labour market is changing. What professions will trade unions be associated with in Europe and the Americas, say, fifty years from now? In your opinion, will the unions be able to maintain the interest of the "workers of the future"?

A: The world of work is changing at a very rapid pace. The decline of jobs in manufacturing, the rise of non-standard and flexible work and the persistence and growth of the informal economy, coupled with changes in employment regulations and behavior and in some cases, limitations to trade union rights have caused unionization rates to fall in most countries worldwide. In some cases, the decline was exacerbated by trade unions’ belated responses to technological changes, changes in labour markets and in social and political institutions.

Probably the most alarming sign for the future is the age profile of trade union membership. Union ageing has been observed in nearly all developed countries. This is the effect of lower unionization rates among young people. Today, workers who leave the labour market are four times as likely to be unionized, than those who enter. On average, in developed countries, of all employed union members, one in five is over 55 years old, whereas just one in twenty is under 25. In some countries the distribution is less extreme, but the general picture is the same.

Data shows that union density rates rise with company size. Recent data for developed economies, show that, on average, 62 per cent of all union members work in large companies with more than 100 employees, 27 per cent in small or medium-sized companies (10-100 employees) and only 11 per cent in small or micro firms (fewer than ten employees). In Germany, France and the Netherlands, over 70 per cent of union members work in large firms. There are exceptions, for instance in Belgium trade unions are better organized in small firms than in large firms. Such variations reflect differences in the structure of economies across countries and the presence or absence of large multinational firms.

Therefore, while what professions will remain, disappear or emerge in the future is important, unions’ success will depend on many factors, among them: the extent to which they connect with young people; whether or not unions can organize more significantly beyond their present strongholds in public services, large companies and manufacturing sectors; and whether or not they can effectively encourage informal workers to organize.

Most probably unionization among employees in public administration, public services, social insurance, education and health services will remain relatively high in many countries. However, to continue being relevant and influential, trade unions will need to respond to at least two major challenges: the digital economy and the way it transforms jobs and employment relationships; and the divide between workers with stable, paying jobs and workers with unstable, poorly paid or precarious jobs, or no job at all.

Their success will depend on a range of factors, including the following:

• Their capacity to respond to the needs of workers in the informal economy;

• How they manage to invent smart ways to use the Web as a tool to communicate with and organize platform workers;

• Whether they can extend membership to ‘own-account’ workers in both the traditional and digital economy and in small and medium sized companies;

• If they can find effective ways to build coalitions with other organizations and movements to protect and promote the rights of vulnerable groups, enable women’s leadership and spearhead green transformation.

Q: Does the ILO have a clear position on universal basic income? Will it protect a person from poverty, or will it raise a freeloader living off the state? Is it economically feasible at this point for any one country not just to carry out a limited experiment, but to implement it on a permanent basis?

A: In recent years, interest in the universal basic income (UBI) has grown in prominence for multiple reasons. With the onset of COVID-19, this interest has been further enhanced, especially as some countries have introduced emergency measures that reflect some of the characteristics of a UBI. However, aside from numerous pilot experiments such as that in Finland recently, a short-lived UBI in Mongolia (2010-2012), and a UBI in Iran (2011-present day, yet with minimal benefit levels), the UBI has not yet made any major breakthroughs in national policy.

At the ILO we understand the intensity surrounding the debate on this issue. The problems that the universal basic income tries to solve are among the ones that the ILO seeks to address: closing social protection coverage gaps, and guaranteeing at least a basic level of social security for everyone.

However, an adequate UBI that can prevent poverty and ensure a dignified existence would come with significant financing requirements. A modest UBI benefit, on the other hand, may risk spreading resources too thinly across the population and provide insufficient support to those who need it most.

While a UBI may have intuitive appeal as a simple solution, in practice this instrument may fall short of its objective of guaranteeing at least a basic level of income security to all members of society. This illustrates the complexity of the debate: not just any UBI will do, and a UBI alone is not sufficient to meet the full range of people’s social protection needs.

Whether a UBI could potentially be one element of a long-term comprehensive social protection system depends on a range of factors. The ILO Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202), adopted by governments, workers and employers of the ILO’s 187 member States, provides excellent guidance for countries that are considering pursuing a UBI or alternative solutions, such as universal child benefits or universal pensions.

Universal social protection does not necessarily require that everyone receives an equal benefit, but can be achieved through protecting people against the full range of lifecycle risks, as long as it is guaranteed that people receive an adequate benefit if and when needed in line with international social security standards, namely the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention No. 102, ratified by the Russian Federation in 2019.

The Trade Union Journal is a bimonthly journal published since 2013 by the editorial office of the central trade union newspaper "Solidarity" (FNPR) and distributed to trade union organisations and social partners, including the Russian Government and the State Duma.